Cosmogonies.

To shed some light on how this works, I’d like to emphasize the machinic and logical aspect. It’s like imagining cores – we could also say software – that play the role of production machines. So many devices designed to produce works “all by themselves”, so to speak, in a mechanical way. To give a simple example, the copy of the dictionary is a production machine. Once the statement has been established and the parameters set, all you have to do is get to work, and things get done, almost “out of the blue”. Moreover, all production machines derive from a generic device that functions in the manner of a cellular automaton. I’m not going to dwell on this notion, which is perhaps too complex to explain in a few words, but I will point out that the first of these is the “cellular automaton”. c. a. was called “the game of life” by its designer (John Horton Conway) in the early 70s. Years later, Greg Egan used this concept magnificently in a world novel: “Permutation city”. Let’s add that a cellular automaton integrates into its design the environment from which it develops, and that its routing, which plays on rules of interaction and neighborliness, produces situations of rapid development, breakdown, cyclic stuttering or even death.

Read more

Having said that, I feel more comfortable describing the production of the “cosmogonies” we’re talking about. The “forms of the world” (flat as a plate, created by God or by gods, the result of the Big Bang, magical or scientifically coherent) are built, astonishingly, on an always identical schema; a postulate from which are drawn the axioms that define their contours. All this follows the mechanics of meaning, except that the postulate that constitutes its source is always pure intuition: unprovable, unverifiable, fortuitous, an absolutely gratuitous intimate conviction. In fact, and without exception, all postulates are equal, and none of them can claim to be true. In fact, a production machine can generate a postulate and test its validity and effects in terms of the shape of the world. This is the game I’ve been playing, not without an ulterior motive critical of everything that makes up the artist’suniverse… I’m convinced that every postulate, whether cosmogonic or artistic, exposes itself as a singularity so absolute that it illustrates, in short, a moment of pure idiocy. The title of the exhibition, There’s no Moon without a Rocket, reminds us that I place my attention not on the manifestation of these worlds, but on what transports us to them.

Extract from an interview with Richerd Leydier (published in ArtPress, N° 368, June 2010).

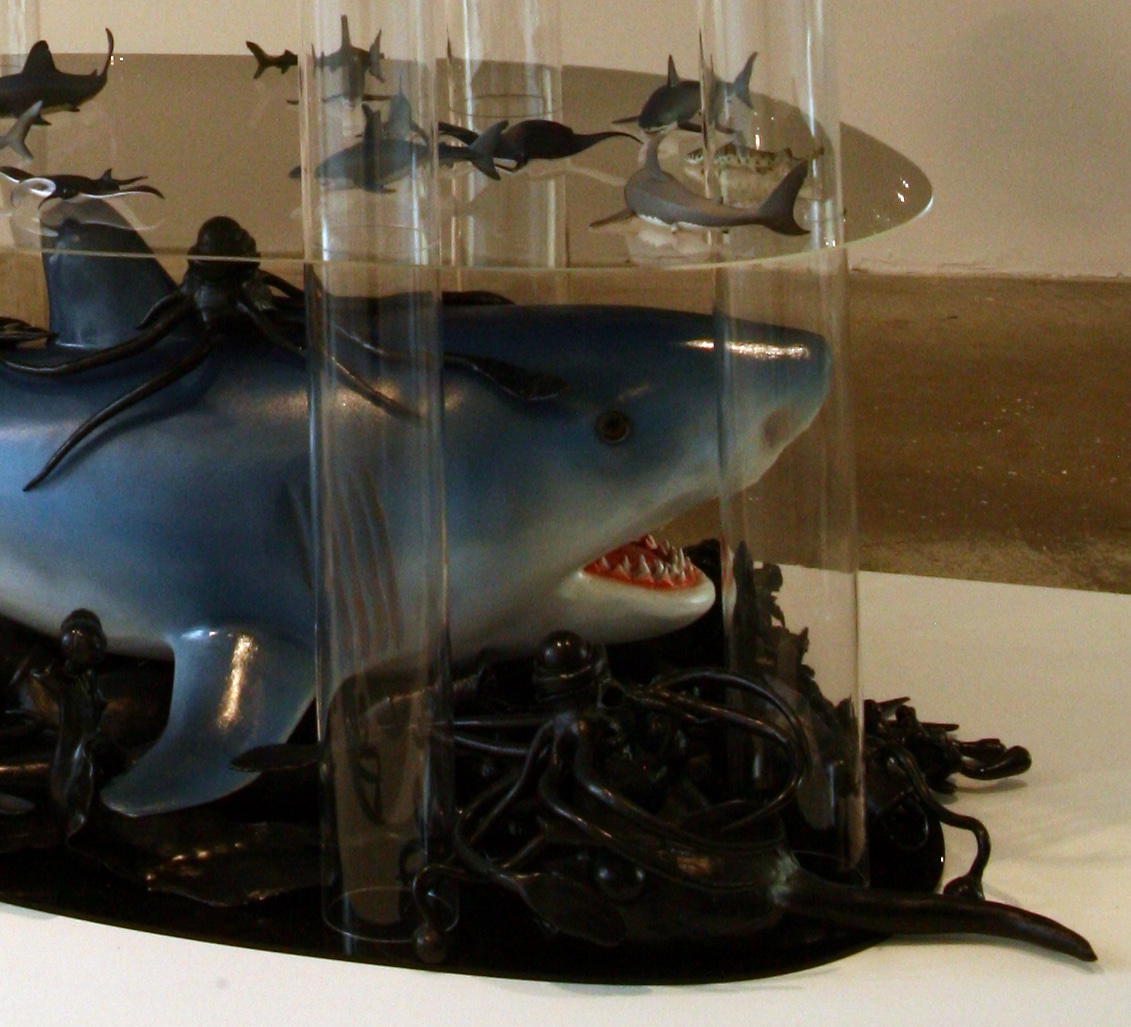

“Asshole World, 2010. Mixed media. 94 x 200 x 163 cm.

“Asshole World, 2010. Mixed media. 94 x 200 x 163 cm.

“Asshole World, 2010. Mixed media. 94 x 200 x 163 cm.

“Asshole World, 2010. Mixed media. 94 x 200 x 163 cm.

“Asshole World, 2010. Mixed media. 94 x 200 x 163 cm.

“Asshole World, 2010. Mixed media. 94 x 200 x 163 cm.

“No Rocket, No Moon”, 2010. Wax, paint. 120 x 57 x 57 cm (In the background, “The Ship”).

“No Rocket, No Moon”, 2010. Wax, paint. 120 x 57 x 57 cm (In the background, “The Ship”).

“No Rocket, No Moon”, 2010. Wax, paint. 120 x 57 x 57 cm.

“No Rocket, No Moon”, 2010. Wax, paint. 120 x 57 x 57 cm.

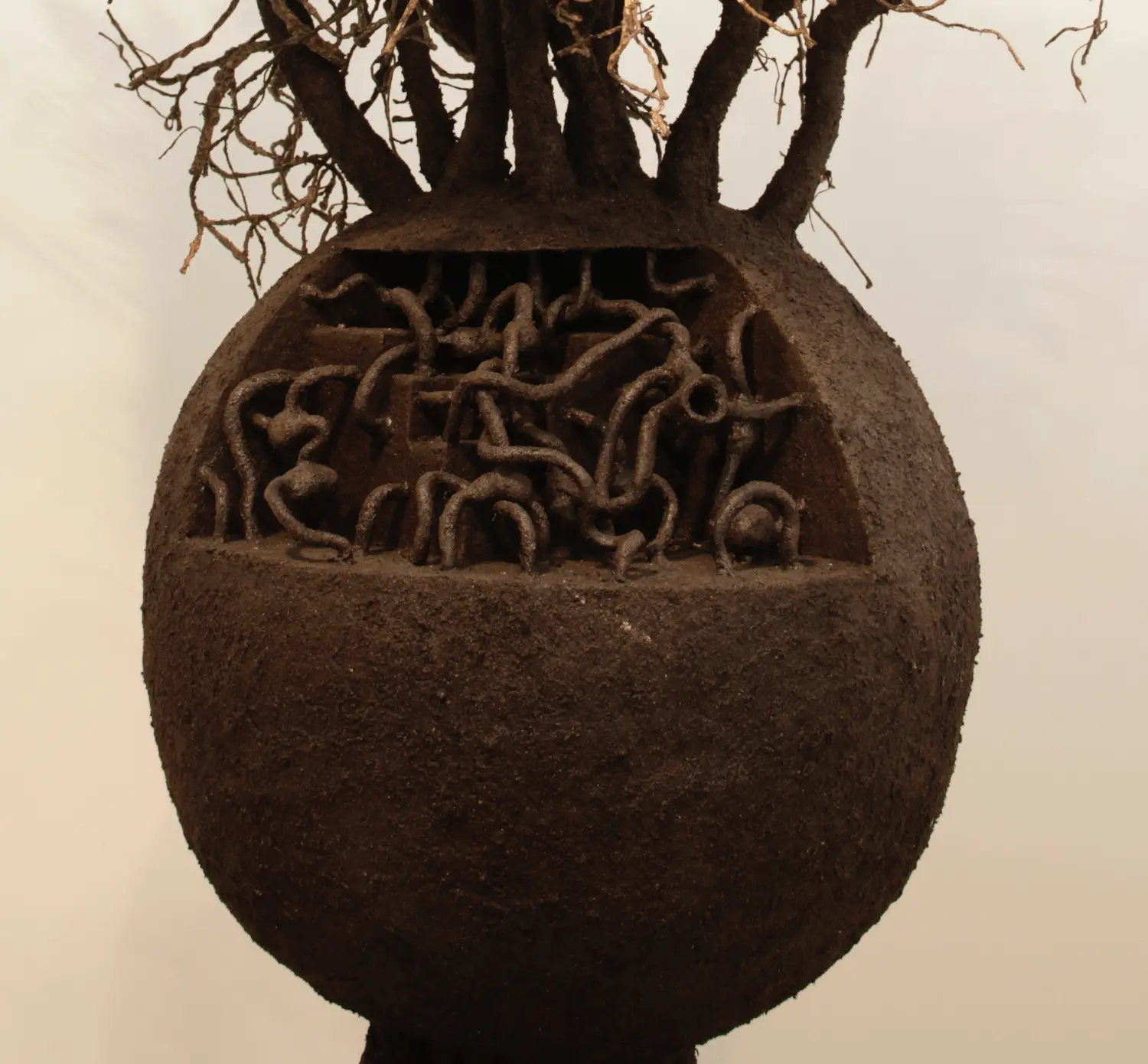

“Dirt World”, 2010. Mixed media. 270 x 130 x 130 cm. (In the background, “The Blender”).

“Dirt World”, 2010. Mixed media. 270 x 130 x 130 cm. (In the background, “The Blender”).

“Dirt World”, 2010. Mixed media. 270 x 130 x 130 cm.

“Dirt World”, 2010. Mixed media. 270 x 130 x 130 cm.

“Flip Flop World”, 2010. Mixed media. 137 x 85 x 185 cm.

“Flip Flop World”, 2010. Mixed media. 137 x 85 x 185 cm.

“Flip-Flop World”, 2010. Mixed media. 137 x 85 x 185 cm.

“Flip-Flop World”, 2010. Mixed media. 137 x 85 x 185 cm.

“Flip-Flop World”, 2010. Mixed media. 137 x 85 x 185 cm.

“Flip-Flop World”, 2010. Mixed media. 137 x 85 x 185 cm.

“Tree World”, 2010. Ilex crenata, various materials. 265 x 165 x 130 cm.

“Tree World”, 2010. Ilex crenata, various materials. 265 x 165 x 130 cm.

“Tree World”, 2010. Ilex crenata, various materials. 265 x 165 x 130 cm. (In background, “ World of Foam ”).

“Tree World”, 2010. Ilex crenata, various materials. 265 x 165 x 130 cm. (In background, “ World of Foam ”).