The Game Of Life

Polygamous trajectories

In 1992, exchanging intentionality for chance, Gilles Barbier infused his activities with a singular guidance system. A multitude of operative processes were unleashed via a checkerboard on the floor, equipped with one, then several pawns, in complete contrast to the logic of media formalization and its native conciseness. Now replayed on a grand scale, the mental machinery involves the whole series of works that this device has generated over the past fifteen years: within the “Cellular Automaton”, a sort of Rubik’s cube split into 427 squares – each of which corresponds to the statement of a piece previously produced or to come – six Pawns are activated, dressed in Gille de Binche, ruffles and other tutus. Sometimes smiling, sometimes grimacing, some of them sit upside down, embodying as many directional configurations as a die can contain.

Read more

Around them, six “Displacement Operators” engage the playful mobilities to follow: the Man-De, this “scribe of history” who never ceases to plunge from his Nagol tower, strikes down a sequence of stamps. Simultaneously, the other operators interact in the form of gutter ball games, multiple-choice “suspenders” and earthy stomachs, respectively determining the direction of trajectories, the number of squares to be covered and the final decision to remake (or not) the pieces selected by this cog. It’s a question of ruminating endlessly on the propensity of the entire work to self-replicate in segments, with a string of clinamens to back it up. The principle of the cellular automaton, which Barbier explicitly borrows from the field of science, enables him to conceive a vast, random playground where each cell constantly redistributes itself according to its surroundings. As a result, versions abound and cohabit, and can be reinterpreted over and over again in the “I’d say even more” mode.

The unfinished motif of the work, if it exists at all, is a proliferating tapestry, escaping through complexities that constantly parasitize, aerate and recombine it. Worse still, the proposals unfold from the outside via “production machines” that manufacture them, so to speak, all by themselves – once the basic protocols have been formulated. Like the eponymous character created by Luke Rhinehart, this is how the artist can launch himself outside himself. The crystallization of choice is less important than its suspension. Each of the operators aims precisely at stretching this lapse of time as far as possible, leaving the decision-making doors wide open: between the release of the marbles and the result they will eventually inscribe, the machine chuckles at the ebullition of the potens, and at the same time guards against definitive options. Locomotion feels at ease, as if in a 4×4 with six independent and interchangeable drive wheels, threatening to break the skin of the cockpit under the plurality of centrifugal dissidences.

Charlotte Serrus (2012)

“The Game Of Life” (third version), 2011. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life” (third version), 2011. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game Of Life”, 2011. Installation. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Centre Georges Pompidou).

“The Game of Life (second version: How to Better Guide Our Daily Lives)”, 1994-1995. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Stiftung Wihlelm Lehmbruck Museum).

“The Game of Life (second version: How to Better Guide Our Daily Lives)”, 1994-1995. Mixed media and variable dimensions. (Stiftung Wihlelm Lehmbruck Museum).

“ How To Better Guide Our Daily Lives ”, 1994-1995. Mixed media and variable size.

“ How To Better Guide Our Daily Lives ”, 1994-1995. Mixed media and variable size.

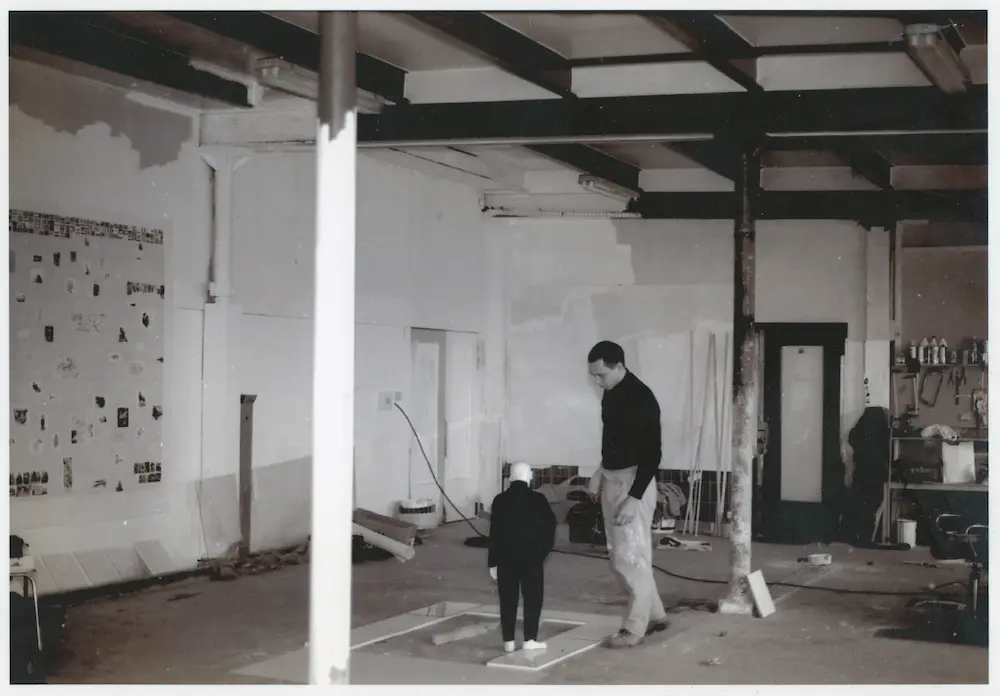

In the studio, 1993, the first checkerboard with pawn. On the wall, one of the first works made with this device: a copy of the 1966 Larousse illustré. Here from “A” to “Alpha”. 1992, ink and gouache on paper, 215 x 215 cm

In the studio, 1993, the first checkerboard with pawn. On the wall, one of the first works made with this device: a copy of the 1966 Larousse illustré. Here from “A” to “Alpha”. 1992, ink and gouache on paper, 215 x 215 cm